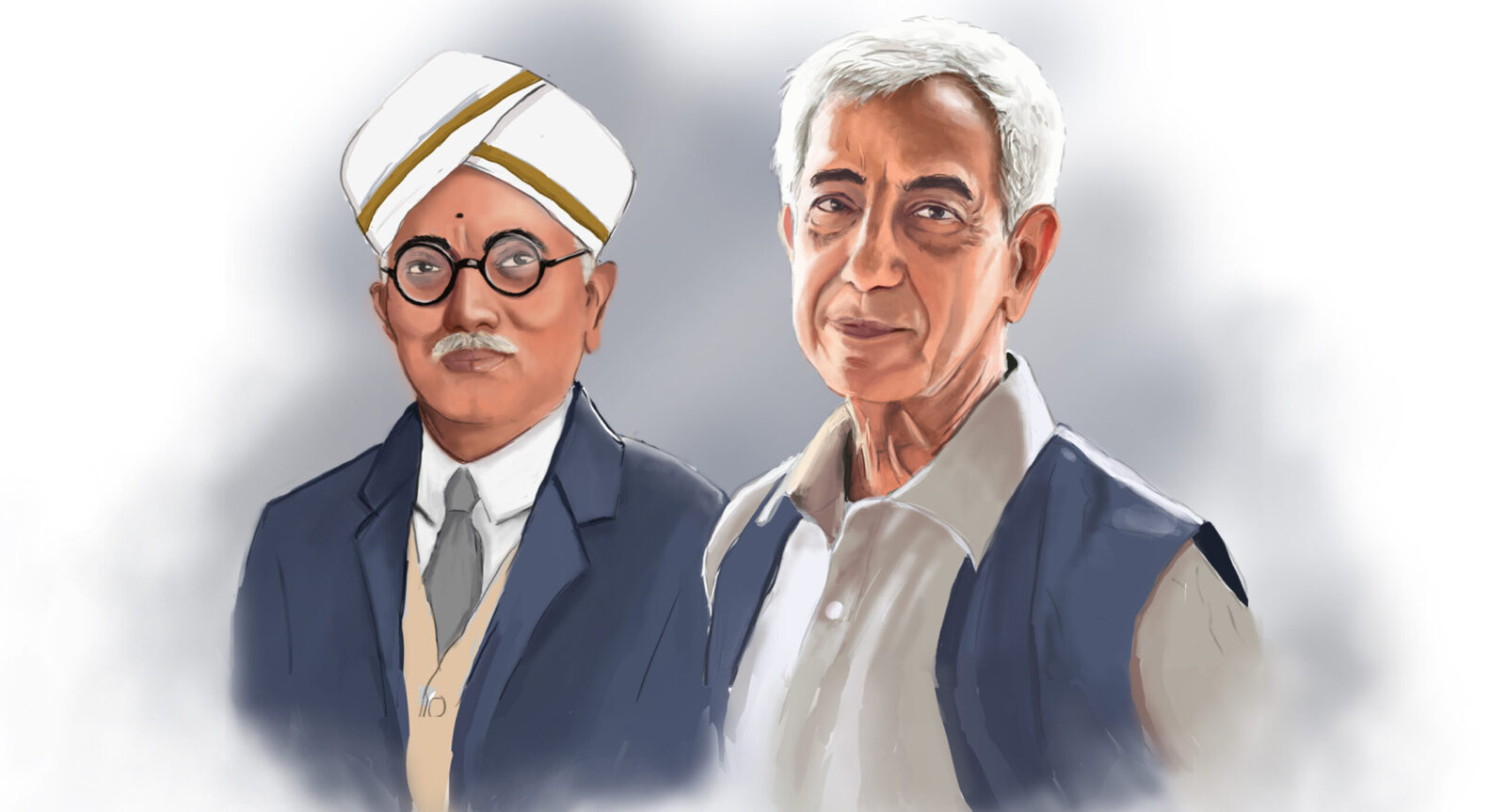

A Tale of Two Architects

S.H. Lakshminarasappa as Chief Architect of Mysore designed many notable landmarks during Maharajah of Mysore Krishna Raja Wodeyar’s reign. Following in his grandfather’s footsteps, Prof. Krishna Rao Jaisim is well known for creating structures that are in harmony with nature. Read about how they both achieved eminence as architects along with exclusive insights into their individual personalities.

Arvind Krishnaswamy

Neha Kaul

Prof. Sudharani Raghupathy, Prof. Krishna Rao Jaisim, Ashwini Jaisim, Maya Gomez, Anu Natarajan, AG Satish

Crossing the Oceans

Liverpool, a maritime city in northwest England is at the estuary of River Mersey and Irish Sea. During the first decade of the twentieth century, the city and the country were in a state of flux. The Victorian era had ended, workers were going on strike, the ‘unsinkable’ Titanic owned by a Liverpool based company sank in 1912, the city had acquired a reputation of having a high crime rate and the First World War was just around the corner.

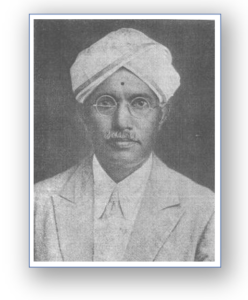

It was in these chaotic times that Srinivasarao Harti Lakshminarasappa sailed across the oceans from India and arrived in Liverpool as a student. Born in 1885, Lakshminarasappa came from a family with an agrarian background in North Salem district. He excelled in studies and earned a BA degree with First Class from Central College in Bengaluru in 1903. An interesting contrast in his performance was that, while he won the Jagirdar of Arni Gold Medal for highest marks in Physical Science, he passed his third language Sanskrit in Third Class! He followed this up with a BE degree in Civil Engineering in 1908, where he was the recipient of The J.A. Jones Prize. This was awarded annually to the candidate who got the highest number of marks in Hydraulic Engineering subject while passing the BE degree (Civil) examination. After graduation, he joined Mysore Public Works Department or PWD as an Assistant Engineer.

It was while he was working in the PWD that he got an opportunity to study architecture in England. In the early 1900s, only about 700 students from India were studying in England. Many of them were scions of royal families from the princely states or from other affluent business families. Most ended up at Oxford or Cambridge to study Law. Some others took courses needed to become civil servants, but few took up architecture.

Lord Lytton’s Report of the Committee on Indian Students 1921-22 documents several problems that they experienced when they came to England like little or no recognition of Indian educational qualifications and no friends or point of contact upon arrival in a strange land. There were changes in clothes to suit the local culture and climate. It was extremely difficult to secure lodging and finding familiar food. Since India was in early stages of the freedom struggle, even displaying sentiments of patriotism was viewed with suspicion and made life very difficult.

Lakshminarasappa arrived in England a few years after more familiar names like Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (in 1888) and Jawaharlal Nehru (in 1905) both of whom studied law at Inner Temple. Listed between Martha Stewart Laing and Jeannette Lancaster, university residence records of 1911 show that he was literally the odd man out. There were no less than 272 students under Faculty of Arts and he was the only one with an Indian name. Picture yourself in his place for a minute and you will appreciate his courage and determination. Being alone in an alien land did not dent his academic prowess and he excelled at Liverpool just as he had done in Bengaluru.

The Liverpool School of Architecture was located on the first floor of the Blue Coat Chambers building on School Lane in Liverpool. Originally built in 1716-17, today it is the oldest surviving building in central Liverpool. The school was headed by noted architect Charles Herbert Reilly for 29 years from 1904 to 1933 and it became world famous under his leadership. The school adapted the technique of Ecole des Beaux Arts, the French national school of architecture. Beaux Arts training emphasized quick conceptual sketches, highly finished perspective presentation drawings and knowledgeable detailing.

Lakshminarasappa enrolled in the Certificate and Degree course, which was the toughest of three courses of study. The entire course took at least five years including practical work. Apart from subjects related to architecture and design, students had to pass English Literature, Ancient History, Philosophy, Physics, Chemistry and Applied and Pure Mathematics. The students also competed in various design contests to showcase their ability and skills. Within a year of joining the university, Lakshminarasappa won the Lever Prize along with three other students for the best architectural scheme for development of Port Sunlight, near Liverpool. This prize was offered by Sir William Lever, the founder of Lever Brothers (known as Unilever today), makers of the famous Lux soap amongst many other products.

In 1912, he was one of only six students to get a First Class Certificate in Architecture, which exempted him from Intermediate examination for membership of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), a global professional membership body driving excellence in architecture. He stayed in the University residences for about four years until 1916 and later at Sinclair Gardens, a suburb in West London according to the Journal of Royal Institute of British Architects.

Return To Roots

Lakshminarasappa returned to India in 1920 and he was conferred the Bachelor of Architecture degree by the University of Liverpool in 1921. Backed by his extensive education, he was involved in several projects undertaken by the Mysore Government.

Even in those days, Government work was not free from its share of controversies. One such war of words was related to Mysore University which was established in 1916 during the reign of Krishna Raja Wodeyar where several new buildings were to be constructed.

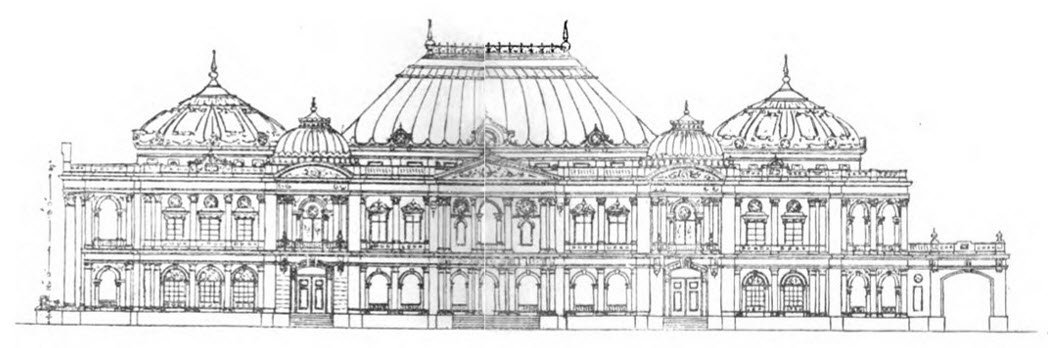

In October 1920, The Builder, a journal of architecture from England published Lakshminarasappa’s design of Krishna Raja Hall as the chosen entry for the Mysore University Senate Hall in an open competition. S.V. Cadambi, the Chief Engineer of Mysore disputed this in a letter to the journal, stating that as a Government official Lakshminarasappa was not allowed to submit an entry. However, the magazine stood by its claim after writing to Lakshminarasappa who confirmed that it was his design that was accepted.

However, this controversy did not end there. Reeking of colonial superiority complex and racial prejudice, The Architect, a British periodical, criticized the design for Krishna Raja Hall, calling it uselessness of educating an Asiatic in European design, a crude mixture of the West and East and the dream of an ambitious jerry-builder (a cheap and shoddy builder). Whether it was a case of sheer arrogance, lack of judgement or plain intolerance, we will never know as the column was written anonymously.

Lakshminarasappa became the Principal of the College of Engineering (known as UVCE today) between 1927 and 1932 and the Chief Architect of Mysore Government soon thereafter in 1935. With three bachelors degrees and several awards to his credit, he was also keen on supporting deserving students. In 1929, he established ‘The Lakshminarasappa Scholarship’, in memory of his grandfather Amaldar Lakshminarasappa (Amaldar was a Revenue Collector during British era) with an endowment of ₹3000. This scholarship was to be given to the student who earned the largest sum of money towards college expenses using his professional knowledge.

In the same year, Lakshminarasappa was also elected as the Dean of the Faculty of Engineering and Technology. Along with his teaching responsibilities in the Civil Engineering department, he was also keen about physical fitness of students. According to information gathered by Vision UVCE, the UVCE Alumni Association, he initiated physical training sessions for students under instructors from the Army. Lacking space, he proposed using the roof of the college building in full view of people on the road, that too in the middle of the day under the hot sun. Obviously this did not go well with the students and the idea was eventually dropped.

Lakshminarasappa expanded the college library from about 400 books in 1917 to over 1200 during his tenure. In addition, he was instrumental in resolving many long standing issues such as financial difficulties of the college, ensuring that the courses met the standards of the Institution of Engineers and recognition of the Engineering degree by Mysore University.

Besides being an architect, an educator and a Government official he was instrumental in bringing together engineers. In 1933, Institution of Engineers (India) did not have a local chapter in Bengaluru but agreed to hold its annual conference in the city only with Lakshminarasappa taking the responsibility of making all arrangements. Due to his untiring efforts, the sessions held at the Daly Memorial Hall on Nrupatunga Road on January 16th and 17th 1933 was a grand success. Maharajah Krishna Raja Wodeyar donated ₹2500 to the building fund of the institute and this opportunity was used to set up a centre in Bengaluru.

In 1935, Sir Puttannachetty Town Hall, a structure in European classical style designed by Lakshminarasappa and built at a cost of ₹1.54 lakhs was completed and inaugurated by Maharajah Krishna Raja Wodeyar. He probably never imagined that, in the 21st century, it would become Ground Zero for all protests in the city. Apart from this, he designed the Bengaluru Municipal Corporation (BBMP) building, the Lakshmidevamma Children’s Hospital within Vani Vilas Hospital and the Forest Research Laboratory on Sankey Road, adjacent to the Indian Institute of Science. Outside Bengaluru, he worked with E.W. Fritchley on the Lalit Mahal Palace modeled on the lines of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London.

What was his design philosophy? In an essay Lakshminarasappa wrote for the Mysore University Magazine he shared his views on architecture starting with Manasara, the Sanskrit treatise on Indian architecture and design which was made up of 70 adhyayas (chapters) and 10,000 shlokas (verses). He drew a distinction between physical (craft) and spiritual (art) aspects of structures built by humans. The principles were classified under Pictorial, Sculptural, Descriptive and Structural categories. He stated that buildings that were not in harmony with its natural surroundings could not be termed as beautiful. In his view, even the definite shadows cast by buildings were part of the whole design as light and shade played a key role in architectural beauty. These principles were even more relevant as he was involved in the design of large buildings of public importance. Other important factors covered in his essay were about Scale and Proportion, Strength and Stability and design guided by tradition. The last point is particularly relevant today as we see incongruities like Spanish and Mediterranean styled buildings in Bengaluru.

Subsequent to his retirement as Chief Architect, he served as one of the three members of the Drawing and Architecture Board of Studies at the University of Madras. The chairman of this board was Laxman M Chitale, a renowned architect from the city of Madras (now Chennai). As you read on, you will see that this professional association of the two families would be repeated about three decades later as well.

Lakshminarasappa encouraged and mentored other promising architects and engineers. T S Narayana Rao, born in Mysore was one such example. Narayana Rao assisted him in the construction of Town Hall, Municipal Office (BBMP) building and eventually started his own private consulting practice, a rare occurrence in those days. He designed Rashtriya Vidyalaya and St Joseph’s College Observatory along with many other notable buildings.

Life Beyond Architecture

It is surprising that very little was written about Lakshminarasappa, a person of such high achievements. He features only in a few government documents; even the Karnataka State Gazetteer which lists Town Hall as one of the notable buildings of Bengaluru does not mention his name anywhere.

Apart from his professional and academic interests, we can deduce a few aspects of his personality by what is known about him. Lakshminarasappa was a person with true perseverance and determination as can be seen by his decision to study at Liverpool despite societal opposition and in difficult times. Judging by his initiatives as the Principal of the College of Engineering (UVCE) he was a disciplinarian. The tales of his opposition to Otto Koenigsberger- a foreigner succeeding him as Chief Architect of Mysore State- showed his streak of nationalism.

The Indian Institute of World Culture, which was just four streets away from his home, listed him as a long time member; so it is possible he was interested in reading and other events organised by them. The 1954 institute report also mentions that he arranged the maiden dance performance of his granddaughter Sudharani in their auditorium on November 20, 1954, after she had completed a two year course under U.S. Krishna Rao.

Mysore Government Horticulture Department documents record that he received about 300 Australian fruit plants in 1936 along with advice for cultivation of fruit plants such as pomegranate, lime, orange, guava, mango and grapes at his Basavanagudi home. Going by the large number of plants, it would not be wrong to conclude that he had an interest in gardening.

However, these are just small pieces of the puzzle that do not give us a complete picture of his personality. For example, we do not know much about his student days at Liverpool. When contacted, Prof. Soumyen Bandyopadhyay, the Sir James Stirling Chair in Architecture and Head of the School of Architecture at University of Liverpool said that a researcher has been assigned to trace the history of Lakshminarasappa and other Indians who studied there.

With the passage of time, we forget personal characteristics of people who are no longer with us. Their work will stand the test of time but memories tend to fade away thanks to the phenomenon of memory extinction. Since Lakshminarasappa passed away in 1961, sixty years have gone by. However, we are very fortunate to get a first hand account of the person that he was, thanks to Prof. Sudharani Raghupathy. She has been one of the finest exponents of Bharatanatyam in India for more than seven decades and recipient of numerous awards including Padma Shri (the fourth highest civilian award of India) in 1988. Despite her busy schedule and involvement in Shree Bharatalaya, her dance school at Chennai, she was happy to hear about this tribute to her paternal grandfather and shared memories of those happy days.

A Towering Personality

When he decided to study architecture at Liverpool, the entire community was unhappy because he would cross the oceans. There was talk about doing prayaschittam (atonement) for this ‘sin’, but he was determined and did not back down.

He had a very towering personality and when he walked into a room everyone would sit up. He was quiet by nature and restrained in his speech. He was so punctual that people would literally set their watches when he went for his daily walk on H B Samaja Road. He was very fastidious and believed that everything should be in its place. You could find things exactly where it was kept years ago!

He never sought publicity despite his brilliance and achievements. It is not widely known but Kengal Hanumanthaiah visited him at home and asked him to design Vidhana Soudha in early 1950s. However, he declined stating he was getting old and wanted one of his brilliant students to take up that responsibility.

He was very keenly interested in astrology and studied horoscopes in detail. He knew pooja mantras well and what was amusing was that if a priest made any mistake he would stop and ask him to repeat it (“ಎನು ಸ್ವಾಮಿ ಸ್ವಲ್ಪ ತಪ್ಪು ಮಾಡಿಬಿಟ್ರಲ್ಲ. ಇನ್ನೊಂದು ಸಲ ಸರಿಯಾಗಿ ಹೇಳಿಬಿಡಿ”). In fact, some priests were nervous to come to our home with the fear of making a mistake and being corrected. Of course, as children we would dread it as this meant we had to wait longer for the proceedings to complete.

In the 1940s and 50s, learning to dance was not very common nor encouraged. Initially my grandfather feared that dance was strenuous and would make me weak in a few years. He was not in favour of it and I had to surreptitiously go out through the back door of our home on H B Samaja Road to my dance class without his knowledge. During the 1950s, a lot of foreign dignitaries visited Bengaluru and I got many opportunities to perform on stage. When Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru personally expressed a desire to see me perform, he was very proud and accepted my passion to learn Bharatanatyam. From that day onward, he wanted to see me every time before I went on the stage for a performance. He did not attend my performance itself but he would make it a point to bless me when I bowed and touched his feet.

He was a wonderful person, very handsome, very versatile in his personal life with a truly overpowering presence. I am very proud to say I was very close to him and knew him well.

— Prof. Sudharani Raghupathy, Grand daughter of SH Lakshminarasappa, eminent Bharatanatyam dancer and Padmashri Awardee in 1988

Born To Design

About four years into his retirement, Lakshminarasappa welcomed a grandson into his family. Krishna Rao Jaisim (Prof. Jaisim hereafter) was born in 1944. One of many siblings in a large family, he studied in Madras Christian College Higher Secondary School (MCCHS) and completed his intermediate (pre-university) education at Agurchand Manmull (AM) Jain College in Chennai. He enrolled in the School of Architecture and Planning which was initially located in Alagappa Chettiar (AC) College of Technology in Guindy. He has stated that architecture was not his first choice until he was nudged into it. In 1966, he was awarded a degree in Architecture from University of Madras, just like his grandfather (even though Lakshminarasappa studied in Mysore state, all colleges came under University of Madras in the early 1900s).

Reams of words have been written about Prof. Jaisim along with numerous interviews. Much of what he has achieved is well known but it is still worthwhile to document a few interesting facts and observations to provide context.

Between 1966 and 1970, Prof. Jaisim honed his architect’s skills at LM Chitale and Sons under Srikrishna Laxman (SL) Chitale. SL Chitale had inherited this business from his father who had passed away in 1960. As you may recall, Prof. Jaisim’s grandfather Lakshminarasappa had worked with SL Chitale’s father Laxman Chitale in the 1940s. The Chitale firm had designed many landmarks with simplicity, functionalism, natural light and ventilation as the core principles. SL Chitale added a touch of modernism to this. The Venkateswara University Auditorium he designed in 1975 is perhaps his most famous project. It would not be wrong to state that these four years played a significant role in the next four decades of Prof. Jaisim’s work.

In August 1970, Prof. Jaisim ventured out to be an independent architect turning down lucrative job offers. During a period when most architects just used their name as a personal branding of their practice, Prof. Jaisim’s choice of Fountainhead, based on a book was both unconventional and adventurous. For those unfamiliar with Ayn Rand’s 752 page magnum opus, it is about Howard Roark, a student of Architecture who is expelled from college because he is intransigent in his views about ‘Classic’ architecture. Bent upon doing it his way, he becomes an apprentice under a brilliant architect whose business is about to collapse. Despite facing years of trials and tribulations, Howard Roark does not waver from his principles and is eventually vindicated. Looking back at over fifty years of Prof. Jaisim’s work now, it can be said that he imbibed the true spirit of Roark’s approach to architecture and put it into practice.

It was a slow start but new clients steadily increased over time. Projects had fascinating names and designs to match. Included in them were ‘Ego’ and ‘Anthem’, his own homes. ‘Ego’ was built on the seashore of Madras with hollow blocks made at the site. In 1980, Prof. Jaisim became a resident of Bengaluru and built ‘Anthem’ two years later in the suburb of Raja Rajeshwari Nagar. It was, in his words, an attempt to give a home to his wife and daughter that they would be proud to share. Then there was ‘Emerita’ which was designed around a jack fruit tree in the living room, ‘Sampradaaya’ based on concept of rotating squares and ‘Epicentre’’ built for ITC at the site of a century old tobacco warehouse.

Perhaps the most well known of them was ‘Guhe’ (Cave), the home of colourful film and theatre personality (late) CR Simha. Since Simha was very popular, his home in the Bengaluru suburb of Banashankari became a mini tourist attraction and every budding architect’s reference point. When it was built in 1990, there were hardly any other homes in its vicinity which made it stand out even more. It was considered unique and remains one thirty years later, even though the city’s uncontrolled growth has all but swallowed it. The design of the house won a commendation in the Private Residence category of JK Cement Architect of the Year awards for 1992. Prof. Jaisim himself steadfastly refuses to pick any single project as his favourite. In fact he once said that every project is like an only child and it needs total personal care and attention.

Quite unusual for an architect, Prof. Jaisim also featured in the Limca Book of Records for designing the largest wine and cheese outlet under a single roof called ‘Not Just Wine & Cheese’ on Brigade Road.

The list of institutional clients is virtually endless including Hewlett Packard, Advanced Micronic Devices, Taj Group, Infosys, Indian Institute of Plantation Management, ITC Infotech and Art of Living to name just a few. Homes of Nandan Nilekani, Dr. V.S. Arunachalam, Anant Nag and Girish Kasaravalli are also Prof. Jaisim’s creations.

Prof. Jaisim’s design philosophy is built around the basic elements of nature. It is reflected in his use of earthy materials such as hollow clay blocks, bamboo, terracotta and stones with a strong emphasis on natural light and ventilation. He thought beyond just the physical aspect of design. Prof. Jaisim once said that he would never build a square shaped room (for his daughter) as that stifled a child’s creativity in growing years. Most interior spaces in buildings are squares or rectangles – shapes that are typically associated with strength, discipline, security and reliability but do not evoke any inspiration, curiosity or fun (think of many of our schools where classrooms are identical boxes).

Being an independent professional architect, Prof. Jaisim’s body of work is more diverse and larger than that of his grandfather who had to work within the boundaries of a Government employee. His work also crossed state boundaries as he was not restricted in his choice of projects.

However, during the years prior to independence, many imposing public buildings were built giving his grandfather an opportunity to design monumental landmarks. How would Prof. Jaisim design a Town Hall if it was built today? That is indeed an intriguing question but we can only imagine the answer.

Much like his grandfather, Prof. Jaisim has also been actively associated with academia. He is the Design Chair at BMS College of Architecture besides being a visiting professor at many other colleges. He has been involved with Indian Institute of Architects in various roles.

What makes Prof Jaisim a nonpareil architect? What is the person behind the architect like? Instead of enumerating all his works and analysing them, we asked these questions to three women who know him well and here is what they had to say.

An Inspiring Mentor

Fountainhead was a microcosm of India with students from all over the country apprenticing under Jaisim. It was a small, beautifully designed space in his home-office, “I Do”, in Jayanagar, Bengaluru.

Fountainhead was the only firm I applied to as a trainee architect in 1993, while in my third year of architecture, intrigued by the name and freshly minted on Ayn Rand’s book.

As trainees, we had to be on our toes all the time, with projects and site visits. Jaisim was an inspiration, very clear in what he wanted and he could spot a good design attempt immediately, while also being quick to call out half-hearted ones.

He had an unfettered approach to design, always responding in a fresh way to the context, which is why each of his projects is unique. I was fortunate to visit a lot of his sites and photograph them for the office. If there’s one definitive thing I picked up from Jaisim, it was designing on a diagonal grid, something I fall back on even today.

Jaisim is as good a writer and teacher as he is a designer and architect, and this wholesomeness in his personality is what sets him apart. He lives his philosophy.

— Maya J Gomez, Architect and Planner, Gomez & Associates Architects

Creating Magnificent Spaces for People

Jaisim was the first architect I worked with. I met him for the first time when he was a guest speaker to our class when I was in my second year of architecture. I was fascinated with what he had to say, intrigued that he called his firm Fountainhead, and made up my mind I needed to work with him. He was instrumental in my growth as a designer and help me understand sustainability and the use of local materials – something I use today in my work.

Jaisim is one of those creative people who don’t let the status quo limit them. He is all about experimentation – his use of hourdi tiles set a standard in the industry. He is bold with his ideas and has a complete grasp on structural systems – where he has the ability to have structural engineers go beyond their comfort zone.

He has inspired hundreds of architecture students to be passionate about their profession. His humility, his passion for his work, his creativity and his convictions are what make him a special person.

I would pick the work he did in Rishi Valley School as one of my favorites. It was the beginning of his long journey in creating magnificent spaces for people to live, work, study, play and meditate in. To put it in his own words, that was the starting point of the continuum.

— Anu Natarajan, Housing Initiative Lead, Facebook Inc

Up Close and Personal

Growing up, I lived in two homes designed by my father. One was ‘Anthem’ and the other ‘I Do’. My room in ‘Anthem’ was the envy of everyone. There was a raised platform that ran the length of the outer circumference of the room. And the walls there were all painted black! I had boxes of coloured chalk and I would spend hours and hours just drawing there. Even the shadows thrown by an air vent in the roof was something special. As the blades moved with the breeze, the shadows spun slowly or quickly, and at different angles depending on where the sun was. Delightful!

My second room at ‘I Do’ was shaped like a piece of pie. There too I had a raised area which was like a small study space. I had a big board for me to pin up posters, shelves, a large wardrobe, and everything that a teenage girl could want. And, true, I never had a square room!

As an architect, he was always traveling somewhere or the other. My father was very passionate about his work, always exploring how different material lent itself to different uses or even the same uses in different ways. Stone, brick, cement, glass, iron and steel – all were flexible and mouldable to him, There were always samples lying around and being tried out in our home too sometimes! He applied himself to his work as a parent nurturing a child. He always became friends with all his clients. I suppose in a way every building was a work of art created with much love, curiosity, and passion. So the bond with the owners was that much deeper.

On the personal side, he was watchful of my overall growth as a person. He always encouraged creativity and never really stopped me from trying anything. When I completed High School, he asked me if I would consider Architecture. I would have loved to have studied Architecture but the requirements of physics, mathematics and chemistry in the following years rendered it moot. He never pursued the matter afterwards as he always said it was my choice.

When I was growing up, architecture was surprisingly not a common topic of discussion at home. My father had varied interests, as did my mother. Both read a lot and would discuss finance, politics, books, articles or about someone of interest.

Even today he is active, but only on projects that interest him and that are worth the time. In other words he is particular about what he works on. But he generally never says no to anything. (And that is also his way with me – always.)

He spends more time on webinars and conferences now than ever before. As one of India’s senior most architects, this is his way of giving back to the community

— Ashwini Jaisim, Daughter of Prof. Jaisim and Communications Professional

I Do

Dominique looked at the gold letters—I Do—on the delicate white bow. “What does that name mean?” she asked.

“It’s an answer,” said Wynand, “to people long since dead. Though perhaps they are the only immortal ones. You see, the sentence I heard most often in my childhood was ‘You don’t run things around here.’ ”

-from The Fountainhead by Ayn Rand

In 2017, Prof. Jaisim published a collection of writings in the form of a book called “I Do”. Edited by his daughter Ashwini Jaisim, the reader is taken on a rollercoaster ride through his mind. Divided into sections called Water, Earth, Air, Fire and Ether, most of it is focused around architecture interspersed with a myriad of other topics. He is quite outspoken in his views on destruction of Bengaluru in the name of development (his emphasis), mindless modern glass buildings (“IT Architecture”), computer technology (“keyboard hammering and mice tickle along all day attempting to realise what a sketch pad can do in seconds”) and bemoans about the lack of civic sense.

Since this is a collection of writings from over twenty years, there is some repetition of topics. Perhaps the only debatable view is on sustainability and the changing planet (“Global doomsday soothsayers are making a killing…”). He wrote it many years ago, but given all the havoc of wildfires, storms, ice melts, floods, drought and other calamities of recent times, it would be hard to accept that viewpoint today. Yes, the methods adopted by the ‘Green Activists’ may not always be correct, but we cannot deny that we are staring at an existential threat if we continue down the path we have taken. Perhaps, he may have a different opinion now as well.

The book offers some interesting professional and personal insights. He believes that the South Indian idli and dosé are architectural marvels of the culinary world and he is an admirer of Frank Lloyd Wright, the visionary American architect. The lack of tradition or INDIANISM in design (echoing what his grandfather said nearly a hundred years ago), use of stone (“noble material”) in construction, importance of light and cost effective methods of construction are other key topics close to his heart. He is optimistic of Bengaluru’s future (“it is the greatest space on earth”) as a city despite all the problems and believes that the city has the most promising and imaginative architects in the country.

There is perhaps no better way to end this tale than a few words from Prof. Jaisim himself. He has an active digital presence, just short of the Facebook limit of 5000 friends and busy as ever. When we reached out to him with a few questions, he readily answered them in his distinctive style.

Reflections

A Brief Conversation with Prof. Krishna Rao Jaisim

Your grandfather Sri Lakshminarasappa was a pioneer in many ways. He studied overseas in England during the days of ‘Kala Pani’ – when crossing the seas was considered a taboo. He was an architect for the Royal family in Mysore and designed Sir Puttana Chetty Town Hall in Bengaluru. What is your recollection of him? Did his achievements inspire you to become an architect?

Yes, Sri Viswesharayya and His Highness Krishnaraja Wodeyar admired the approach of Sri S H Lakshminarasappa to sketches and scale and encouraged him by sending him to Liverpool to study architecture. He went on the ship doing prayers and other religious clearances. He studied in depth to a point fifty years later. The School of Architecture somehow found me and collected whatever was left of his archives and is now part of their Library. He was one of their top students. He designed many buildings including Lalith Mahal and Vani Vilas Hospital. His name is there in a few hidden stones. His daughter Namagiri Bai, my mother decided that I should study architecture (that is another long story).

Your grandfather designed many landmarks in the city. When you think of them do you have any favourites or perhaps what you think is his best work?

He was very good in detail and clarity and classical style. And his works were very erudite. Lalith Mahal, Town Hall, Vani Vilas Hospital and many residences were remarkable.

Srikrishna Laxman Chitale, the renowned architect was your mentor. How did he influence your work?

SLC was a phenomenon. He took me on as a challenge and gave me the freedom to explore and express myself. Great in detail he was, and I in my abstraction fused them. He made me think with guts.

Today we have sophisticated software that can help in design and visualisation. Does this help in making a better architect or has it changed the way architects approach design?

Tools are a media of convenience. The mind and the way one thinks is the only path to great architecture.

Ayn Rand’s Fountainhead is about a young architect, who battles against conventional standards and resistance to innovation. Did you see yourself as one when you called your architectural firm as Jaisim-Fountainhead?

Yes, Ayn Rand’s The FOUNTAINHEAD opened my vision to question and explore. Fear and Failure were forgotten. Studying various aspects of life, environment in context and content was and are the only spaces of time that mattered.

When you look back at over 50 years of distinguished career as an architect, would you do anything differently in hindsight?

I have learnt and continue to learn. Each had its own content and expression in context of time, space, and environment. It has been wonderful exploring my thoughts from your in depth queries. Thank you for the opportunity.

Image Above: ITC building designed by Prof. Jaisim

Sources:

- The Builder, October 27, 1922

- The Mysore University Magazine, Volumes 11-12, 1927

- The Architect, A Journal of Structural & Decorative Art, July to December 1920

- The Calendar, University of Madras, 1945

- Mysore University Calendar, 1937

- Calendar, University of Liverpool, 1924

- The Architect and Building News, 1912

- Architecture+Design, Volume 22, 2005

- Limca Book of Records, 2003

- Fort Saint George Gazette, 1963