Lockdown 1898

How an epidemic ravaged Bengaluru

It is not very often that events become an existential threat to life as we know it. The asteroid that killed the dinosaurs, world wars, nuclear strikes are some cataclysmic events that come to mind. The COVID-19 pandemic we are experiencing today falls into that category. We all know someone who got infected, lost their livelihood or even worse succumbed to it. Life has become ‘before’ and ‘after’ the pandemic. For those who were too busy to stop and think about life, this has been akin to slamming the brakes at high speed. It has been an rude awakening for many of us. This is a true transformational moment that shows the power of nature. But it is not the first time this has happened. Our ancestors in Bengaluru experienced something similar 123 years ago.

Pandemics and epidemics have been part of our life for centuries. Going back in time, one of the earliest recorded outbreaks was the Plague of Athens which is reported to have wiped out a quarter of the entire population. Thereafter, once every few hundred years, this has repeated sparing no country in the world. Perhaps the worst pandemic in recorded history was the Black Death plague in Europe and Africa in the 14th century which is reported to have killed up to 200 million people.

India has seen its share of devastation and Bengaluru has not been immune to mass outbreaks. August 12, 1898 is one such black day in the history of Bengaluru when plague made its appearance in the city.

Plague is a disease caused by the Yersinia pestis bacterium. It is usually passed through rodents’ fleas or other animals handled by humans. Plague is found on all continents except for Oceania. Over centuries, plague has destroyed entire civilizations but is more uncommon now thanks to improved sanitary conditions and antibiotics.

Even though the current pandemic COVID-19 is caused by a virus, what is common is that both can be spread from one person to another when an infected person coughs and releases droplets that can infect others. Both resulted in people being isolated and immense pressure on medical facilities. The 1898 plague also resulted in some positive outcomes for Bengaluru as new, well planned extensions were added to the city. Telephone services were first started to assist in anti-plague operations.

What has also not changed over a hundred years is how people react to such outbreaks. There is denial (it does not exist or nothing will happen to me), disobedience (why should I listen to anyone or behave as instructed) and deviousness (evading testing or being dishonest about infection).

The very first case of plague in Bengaluru followed the railway line from the west. Before plague reached Bengaluru, the epidemic had already become serious in several places like Pune, Hubli, Dharwad and Belgaum. All these places were connected to Bengaluru by rail. Hence trains were inspected for sick people and some were detained for observation. Even those who did not seem infected were escorted home and observed for 10 days. Despite all this, Bengaluru was not safe. It is said that the servant of a Railway Superintendent was Patient Zero. Soon, the disease spread mainly affecting areas around Goods Shed such as Akkipete, Balepete, Fort (City Market) and eventually to Ulsoor. These areas were overcrowded and congested with narrow streets and houses with no space around them. Shops selling grains in the old city area were infected and moved to the new Tharagupet area. Permission for traders to re-occupy the old shops were given only after disinfection.

Six weeks later, the first case in the Cantonment area was reported. Then, the disease spread like wildfire and the situation quickly got out of control. In the overcrowded areas of the city, the disease spread even more aggressively. Attempts to isolate infected persons resulted in opposition and rioting. About 49 people were arrested in Chikkaballapur for rioting and jailed in Bengaluru.

At the news, there was general panic and over 25,000 people fled the city. Just as today’s border restrictions between states failed to control the spread of COVID-19, authorities back then realised that railway or road inspections helped detect only a handful of cases. From August 1898 to July 1899, over 225,000 people were examined on trains, 11500 were detained but only 66 of them actually developed plague, which was only 0.03%. Passengers were inspected several times during their journey and plague passports were issued at their destination. If a passenger came from an infected area, he or she had to appear at a notified area for 10 days for further observation. People gave false addresses in the hope of escaping observation. Some people even jumped off trains before stations to avoid inspection.

Initially those who were plague infected also refused to be isolated and admitted to plague hospitals or camps. Over time, through education and awareness drives, segregation became acceptable to most communities with the exception of Muslims. Home isolation proved usually fatal to patients and was also frequently violated. People started to even conceal deaths by abandoning or hiding bodies. This resulted in scenes straight out of nightmares and horror movies. A dhobi was stopped with his donkey carrying what seemed to be suspiciously heavy bundles. On inspection, it was discovered to contain his wife’s body which he was hoping to dispose of and avoid segregation and disinfection. It was not uncommon to see bodies on the streets. Carts were used to collect these bodies at regular intervals.

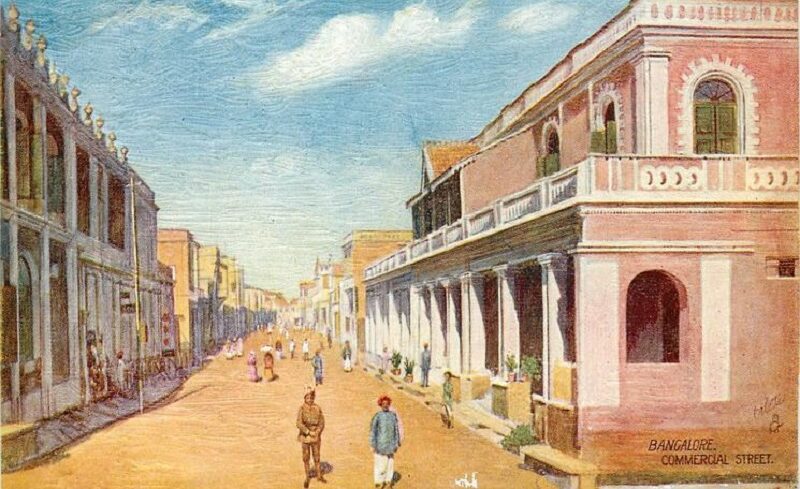

Hard to believe but at the corner of tony Commercial Street of today, victims were sometimes piled up in a heap awaiting the arrival of the cart. When the epidemic was at its peak, huge pits were dug and bodies were emptied into it. History is repeating itself when we see similar scenes happening all over again in today’s Bengaluru.

Rev Henry Haigh writing in the Methodist Recorder described the city during the epidemic as follows

“Instead of the thronged bazaar and teeming streets an ominous stillness prevails. The shops are shut, the house doors are locked, the law courts and schools are empty; no vehicles are running and the few foot passengers seen here and there but add to the desolate appearance of the city. As we drove along, we saw on house after house and on both sides of the streets a great letter “P” rudely painted, with a date inside to show when plague had appeared there. Close beside the “, there was usually a great “D”, telling that the attack had been fatal. All who could leave the city had done so; and in a part of the city usually containing 80,000 to 90,000 people, not more than 10,000 to 12,000 remained.”

The city had a total population of about 84,000 and a total of 7137 cases (3300 in the City and 3837 in the Cantonment area) were reported. Of these 1963 cases were admitted to hospital and 1261 died. At the same time, it is said that over 50% of the cases went undetected.

The statistics of the outbreak seem much smaller compared to COVID-19 numbers we see on television today. But just to put that in perspective, Bengaluru’s population today is around 12 million. If the same percentage of people were to be affected today, there would be over 1 million infections and 180,000 deaths.

People thought that the British were casting a spell on them as so many of them died while plague hardly affected the British. It took some time to understand that the cause was more about insanitary conditions and congested living than about superstition.

Even in those days, people regarded the inoculation with suspicion and dread with rumors flying around, despite efforts of officials to reassure them. In some places, inoculation drives became social events rather than a disease control measure. Sweets, cakes and fruits were given away to attract people to get inoculated at places designated for mass inoculation drives.

Plague Camps were set up to check the mortality and spread of the disease. The largest one called North Camp, capable of accommodating about 700 patients was set up on Magadi Road at a cost of ₹500 per patient. Another called South Camp was setup on Mysore Road but just as it was completed, plague decreased and it was not used.

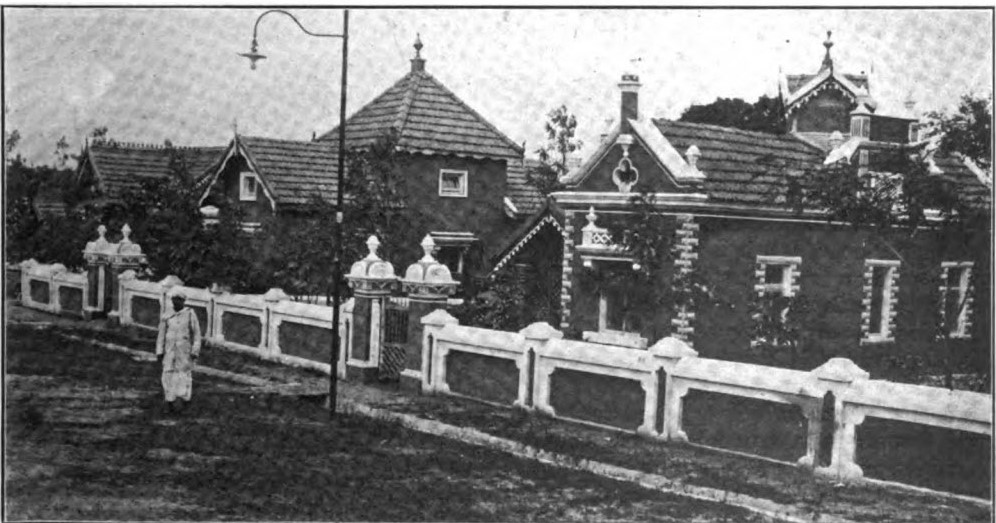

Dewan Madhava Rao who was the Inspector-General of Police was appointed as Plague Commissioner to direct the operations to control the disease outbreak. One of his measures to combat the disease was to move the people from old, crowded localities to new extensions where houses were built on sanitary principles in open areas. These two extensions were Malleswaram and Basavanagudi. A total of 731 acres (440 for Basavanagudi and 291 for Malleswaram) capable of accommodation for 20,000 people were laid out. For people who opted to move there, one year’s salary was given as advance to help in construction of new homes. Sites were sold at a rate of one rupee per 100 square feet.

Apart from this, Fraser Town was developed as a ‘plague-proof’ town in 1906. About 50 acres of agricultural land was acquired for building about 500 houses, most of which was intended for the poor classes. The main roads were about 100 feet wide and the side streets were at least 33 feet wide. Sites were about 2200 square feet for smaller homes and twice that (4400 square feet) for larger ones. Only one-third of the site could be used for actual construction keeping open space all around. The entire area was designed to be free from dampness with good drainage keeping the buildings dry even after heavy rains. Homes were built at a height with stone basements to keep out rodents. Flooring was made of stone slabs or tiles to prevent burrows. Finally, all homes had Mangalore tiles which made it waterproof but let good air circulate inside the home. Sir Harcourt Butler, head of the Sanitary Department announced that Fraser Town was the only plague-proof town in all of India at the time.

The impact of the outbreak was so severe that the city’s population reduced by 25% between 1891 and 1901. Plague did not last as long as cases started to decline by the end of 1898. There was occasional recurrence of plague in and around the city until 1906 but on a much smaller scale.

Those who experienced this are no longer with us today. But COVID-19 has shown us what they must have gone through in those dark days.

Dewan VP Madhava Rao

VP Madhava Rao was born in 1850 and came from a Maratha Brahmin family that emigrated from Satara to South India. After earning a BA degree from Madras University, he joined Mysore Service as a clerk. Very soon, he was noticed as an able worker and quickly rose to the position of a judge. Later he was posted as Deputy Commissioner of Shimoga District where he excelled as an executive officer for about 7 years. He was then made Inspector-General of Police, with the honour of being the first Indian to hold this post. He reorganised the police force, established the Police School in the city. Due to his fame as a capable administrator, he was appointed as Plague Commissioner where he displayed his powers of organisation and administration. The Government of India conferred the Kaiser-e-Hind gold medal for his services. He served as Dewan of Mysore between 1906 and 1908. As an individual, he was a people’s man, broad-minded with sympathy and a large heart. He was a devoted follower of Sri Shankaracharya.

It is thanks to his vision that Basavanagudi and Malleswaram are part of Bengaluru today.

Commercial Street – Then (above) and Now (below) was an epidemic hotspot. Historical reports state that bodies of plague victims were piled up at the corners of this street in 1898

Main Image: A plague patient in the Magadi Road camp, by E.F.H. Wiele

Sources:

- The Imperial Gazetteer of India Provincial Series Volume 19, 1908

- Popular Mechanics, September 1908

- Report on the Health of the Army Volume 40, 1900

- Report of the Chief Inspector of Mines in Mysore Mysore (India : State). Department of Mines and Geology Published: 1901

- JH Stevens, Engineer, The American City, Volume XXVI, No. 3

- The Hindustan Review, Edited by Sachchidananda Sinha Volume XIV, July to December 1906