While growing up, did you always have a creative mindset and want to be an artist?

You have stated that you almost accidentally got into performance photography or performance art in the 1990s. Looking back thirty years later, has it brought you creative satisfaction?

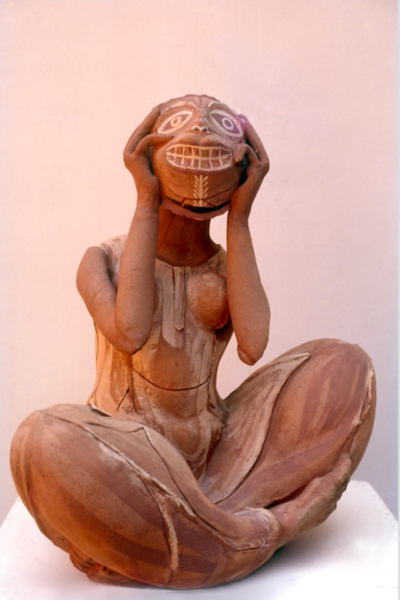

I trained as a sculptor in Baroda and had won a lot of appreciation for my terracotta figurative sculptures. In the nineties, after the Babri Masjid demolition many of us were disturbed by increasing communalization and violence and felt that the organic forms of making art like painting and sculpture were not enough to express the increasing fragmentation of society. My sculpture became more minimal and conceptual, and then I became drawn to conceptual photography. My first photo-romance, Phantom Lady or Kismet was made for a show on cinema, for a lark. I then started exploring this further as photography is more fluid than sculpture and I could put in many interests and use narrative. Each work led to the other, and I always give myself a challenge to go outside the box with each work. It’s lot of fun in retrospect but while doing it, exhausting hard work! Of course, I love it. But I work in many different forms- performance photography, video, sculpture, live performance; I write, lecture, organize talks and seminars and curate exhibitions. They are all different ways of engaging with society, and intervening in the discourse. They have different rhythms. You have to work out systems for each one.

How did you select a theme or an idea for a (performance photography) project? Did you plan the end result (something like story-boarding) or did you improvise during the shoot?

How long did it take for a typical project from conception to completion?

Amongst your various projects, which one was the most challenging and why?

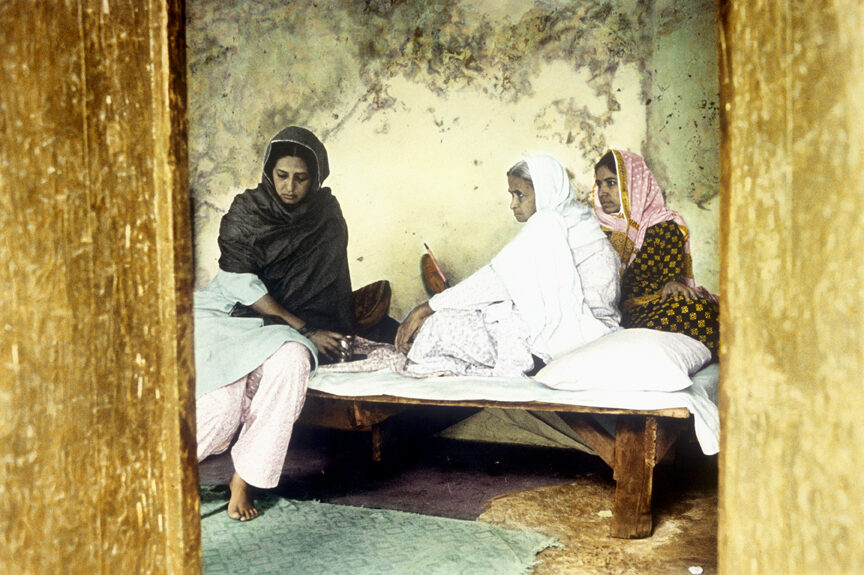

It was Native Women of South India: Manners and Customs (2000-2004). I think I plunged early into a very complex conceptual project without any experience in production work. It was a lot of research too. I had made some photo-romances earlier which were shot on location. This was a project which took off from the idea of the traditional portrait studio as a space for fantasy where an elaborate set would be recreated from an existing image of the ‘south Indian woman’ taking from various sources, like art history, film, theatre, literature, popular culture, anthropology. It took several months and working with different kinds of artisans and technicians, to create the sets, props and costumes as closely as possible to the original. I must have worked with all the people who create the popular visual culture of Bengaluru! As I kept working the project became more and more elaborate and resulted in more than two hundred selected photographs in four series which deconstructed the original image with humour and play. When I started working with photo-performance, it was taken as a joke but with this series which brought in so many ideas into the cultural scene my work became established as serious. It is the most well-known of my works, has been shown widely internationally and is being taught in universities around the world.

Directing while being in the scene is not easy. How did you manage being in front of and behind the camera at the same time?

I do two different kinds of shoots. For the photo-romances which are shot on location, usually public, I have notes prepared and I go and do ‘recces’ by myself and with the photographer and work out the shots. Then there the shoots inside my studio which are usually elaborate tableaus with sets, props, lighting and costumes.

People have asked me if I get into a meditative state while performing. Actually, it is chaotic in the studio, as there are sometimes sixteen or twenty people for the shoot- the photographer, make up man and his assistants, the lighting guys, my artist friends who come to perform in the work and assist me. I am constantly barking orders and giving instructions. What I do is to have reference pictures and ask a friend to check the pose and gestures. We do some rehearsals, and every now and then, I check the results and keep reworking till we feel we have enough material to edit.

Basically, I shoot a lot for each scene, and select the best images. Sometimes, when I am not happy with the results, I rework and reshoot.

You portrayed a lot of diverse characters from different periods - mythological to modern. Even though you use still images, it had elements of mystery, drama and humour. How did you bring the characters to life with the right mood and expression?

I was shooting The The Navarasa Suite at the India Photo Studio in Mumbai, whose owner J H Thakker used to be a publicity photographer for Hindi films in the ‘1950s and ‘60s. When I was trying to create the different rasas they looked like grimaces. So, in desperation I rang up Shanta Gokhale, the theatre critic and writer and asked her what to do. She told me that all the rasas look similar anyway, and it is the context that gives the meaning. She said I must internalize the emotion and not make it too exaggerated.

What I do, is create a mise en scene with a location or painted backdrops, costumes, props, cast, and lighting. I select the style of the photographic image- ie, film noir, sentimental, melodrama, ghost story, action, slapstick, etc. I can’t act, and I do not use professional actors, they are all friends. I like our clumsy body language; it is more real. A mood is created with all these elements, and gestures. For Navarasa I used Thakker’s own early style of Hollywood glamour photography. When I was shooting Kichaka Sairandhri in my studio based on Ravi Varma’s painting, I had to reshoot, because we got so involved with the lighting and camera angles that the characters had no eye contact and were staring in different directions. The photograph made no sense, perfect as it was aesthetically, as there was no psychological charge.

How did you visualize the images - a couple of interesting photos that come to mind are in the Phantom Lady / Kismet series: the shadow of the don with the vamp, the waiter in the restaurant or the customer at the next table. How did you actually think of having them in the scene?

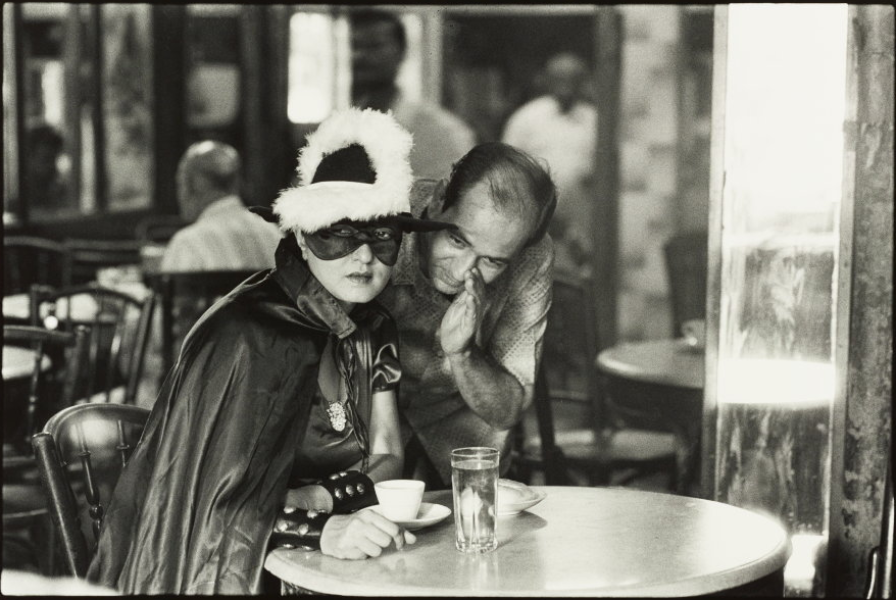

Phantom Lady or Kismet is a thriller shot in the film noir style, which is very expressionist and moody, and uses strong contrasts of black and white, angled shots, reflections and shadows. These elements are used throughout the story. In film noir it is almost a cliché that the villain’s shadow is ominously cast on the wall. I love using clichés.

The waiter scene was shot in my friend the late film critic Rashid Irani’s Brabourne Restaurant in Mumbai. We went there to shoot early on a Sunday morning and found it crowded with customers. Since in my photo-romances, I have a very limited number of performers, I like to include the public to make the images more complex and expand the milieu. Different classes and types of characters then come into the story. Most people are hams and are delighted to be part of any shooting. In another scene, my photographer and I went to recce in Flora Fountain in the evening and fixed the shots and locations. When we actually shot there around 4 am the next morning, the covered pavements had rows of homeless people sleeping there. The fictitious and absurd chase sequence between the Phantom Lady and the Don became charged with the grim reality of the city and made the image infinitely rich.

A lot of my friends perform in my works, which becomes like a private joke, and a record of the time. I got a bit of history when Safdar Hashmi’s mother acted as the controlling mother in Dard-e-Dil which I shot in Chawri Bazar in Delhi. The male character was a well-known Pakistani economist friend, Akbar Zaidi, researching in Delhi at the time.

Your work has been displayed both in India and abroad. Did you see a big difference in audience response to your work?

It’s very different in every place that I exhibit because the cultural points of reference are different. I use a lot of allusions from history and what is called ‘cultural memory’ which connects immediately to the audience, along with the humour and theatricality. My photo-romance Dard-e-Dil is a tragic love story which was found very moving by Indian audiences, because the idea of a joint family, grown up single children living with controlling parents is very familiar in this culture. The audience in my New York show it thought it was hilarious. In my installation The Arrival of Vasco Da Gama, shown in the Kochi Biennale, western visitors were shocked by my notes on the blackboard which attributed Vasco da Gama’s knowledge of navigation to Indian and Arab mathematical schools. It became notorious as the ‘blackboard room’. Vasco Da Gama is an icon in the West who initiated colonialism and their later prosperity. Indian and Asian visitors however were very interested in this critique of colonial history. Director Ong Keng Sen invited me to show the whole project in a solo show during the Singapore International Theatre Festival- Singapore of course, being an important historical port for the spice trade.

Performance Photography has been around since the 1950s. Do you have any favourites or admire any other artist in this space?

I connect myself in general to the history of feminist art. Feminist artists have really developed live performance and performance photography/ video over the years. When I started working with the form in the 1990s, there were many artists all over the world making work in this way, and it was an interesting possibility. I have been strongly influenced by Bhupen Khakhar and felt that no one had followed up on his playful performative experiments in the ‘70s which I loved (posing as Superman, advertising toothpaste etc). Phantom Lady started off from this. I like Gilbert & George’s work and Cindy Sherman’s early Film Stills.

Are you planning any new project either in sculpture or performance photography?

You have been a long-time resident of Bengaluru which has gone through a radical transformation over the decades. Can you share some autobiographical or episodic memories?

I am not really so sentimental about the old pensioners paradise of Bengaluru. I think it is ugly now but vibrant and more of a metropolis. I have a large family here which used to spy on me and report to my parents! I ran away in 1977 to study in Baroda and never wanted to come back. However, looking back, my early years here have influenced me profoundly. I was a teenager in the 1970s when the city was the centre of the New Wave cinema movement, new theatre and the Nayva (Modernist) and Dalit movements in Kannada literature. It was the days of the Emergency and Prasanna had started Samudaya, the most important left theatre group in the country. Actress Snehalatha Reddy, who had played the role of Chandri the Harijan woman in Samskara, the first Kannada New Wave film directed by her husband Pattabhirama Reddy, was arrested on trumped up charges and jailed. When she died soon after being released, there was a big protest march by all the leading citizens of the day. Their son Konarak was our friend and we used to meet there often. The Reddys’ cottage off St. Marks Road was a meeting place for artists and intellectuals. I first met Dr U R Ananthamurthy there.

Bengaluru has always been a centre of cultural experiments and intellectual discourse even in its provincial small town days. (Girish Karnad once remarked that there was no urban literature in Kannada because Karnataka lacked a metropolis). I used to hang around as a young teenager with a bunch of disreputable friends called the Chod gang in Central College. The English Department had teachers like the Navya writer P Lankesh and TG Vaidyanathan (TGV). TGV was a very influential intellectual with a devoted following, and I was a kid at the edges of this group. Cinema was discussed hotly and a large group would go and sit in the first row to see New Wave films which were commercially released in theatres like Rex and Blue Diamond. I saw Satyajit Ray films in Rex morning shows, Awtar Krishna Kaul’s 27 Down and Federico Fellini’s Amarcord were released in Blue Diamond. K N Hari Kumar and several others were also part of the TGV group who went later to join Jawaharlal Nehru University which had newly opened. (He was in the rival Void Gang, so called after their music band!). P Lankesh is of course legendary. I acted in a play directed and translated by him, Aristophanes Lysistrata. I was in the group scenes in the chorus. It was about Lysistrata who leads a women’s rebellion to stop the Peloponnesian war. The women refuse to sleep with their husbands and cause havoc. In the war between the sexes, I actually threw a pot full of water on stage on an actor, instead of pretending to. It seems the play was full of foul language which we didn’t understand, and a family friend wrote a damning letter to the Deccan Herald which infuriated my father and put paid to my budding theatrical career. Not that I could act really. P Lankesh went on to make several New Wave Kannada films and many of the students who acted in this play were in them.

When I was doing my graduation in Mount Carmel College, I was part of a play, Herman Hesses’ Siddhartha, adapted and directed by a member of the Chod gang, Rajashekhar, and we used to have rehearsals in the Holy Cross Christian Boys Hostel building on St. Marks Road. I was in the group scenes (but very dedicated). Balan Nambiar ran evening classes called the Bangalore Art Club in the big shed where we rehearsed, which I later joined. He told me that I had talent and should study art seriously and go to the Faculty of Fine Arts in Baroda. He advised me to wait till I got my degree so as not to upset my parents, got the entrance forms for me, and convinced my father to send me off to live in a hostel in a faraway place. Recently, during my lockdown studio cleaning, I came across a bunch of life studies that I had done in my 1970s Balan art class days. I am now using the drawings in a new project which will draw from various strands of my art practice.

My years in Mumbai/ Bombay after Baroda were also very rich. I was married to a film scholar, Ashish Rajadhyaksha, and was part of a large group of people working with the new wave filmmakers Kumar Shahani and Mani Kaul, who were some of the leading intellectuals in the city. I played a bit role in Shahani’s 1998 film Khayal Gatha as the River goddess Rewa. Mumbai was still the cultural and intellectual capital of India in the 1980s and ‘90s and I was in the centre of the art scene. I was living in a major metropolis for the first time and soaking it all in.

I moved back in 1996 after building my studio here, after twenty years away. My father had been haranguing me to build on a plot he had bought in the boondocks called Ideal Homes off the Mysore Road. Gauri Lankesh lived nearby and we became close friends. My then husband and several of our friends founded the Centre for Society and Culture- CSCS- which became an important centre for cultural studies. When I moved into my new studio in 1996, Prasanna told me sarcastically that I should name it Somberikatte (which literally means Idler’s Platform in Kannada) because he said we artists just hang around the whole day smoking and idling. I loved the name and started a fictitious institution by the name through which I organize lectures and seminars. In the late 1990s I had a series of Sunday afternoon seminars in my studio around the Idea of the Folk where three speakers presented formal papers around a discipline around the idea of ‘the people’ followed by discussion. When I see the roster of speakers it is like a who’s who of Bengaluru. Madhav Gadgil, Ramachandra Guha, Nandan Nilekani and many others – it shows how small a town it was in those days, when people trekked across the city where all the roads were dug up, on a Sunday afternoon to meet and discuss ideas. More recently, to celebrate 20 years of Somberikatte, I organized an international seminar ‘Mysore Modernity, Artistic Nationalism and the Art of K. Venkatappa’ at the NGMA Bengaluru in 2016. The book, the first major study on the artist, edited by Deeptha Achar and myself, will soon be published by Routledge.

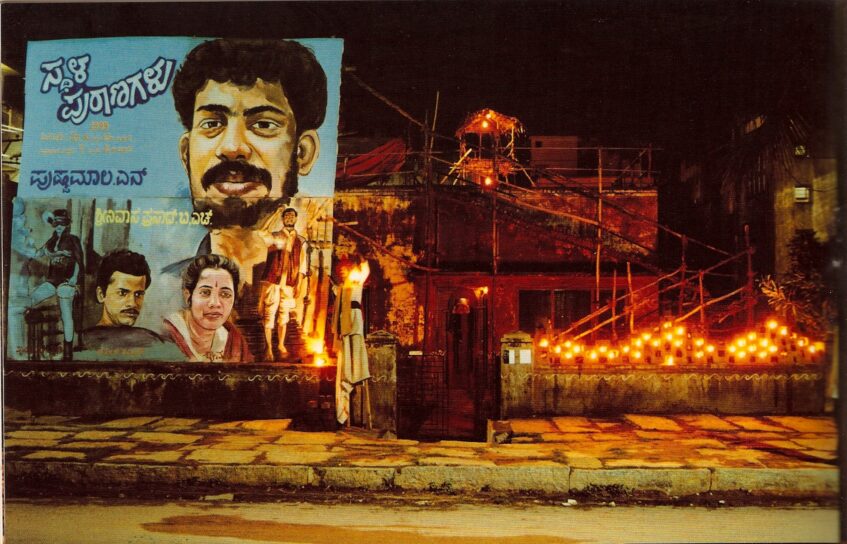

Many people from different fields moved to Bengaluru in the 80’s and 90s and several of us who had lived away in different places moved back. New institutions were coming up. Many young scientists, artists, architects, designers formed groups to organize things. From the ‘90s Bengaluru became an experimental art hub where young artists were doing huge land art and site-specific works, live performance and installations and creating artist spaces, organizing Kala Melas and international workshops. In the mid ‘90s the city looked like a war zone, every pavement dug up, flyovers being built. Bengaluru had a strangely amorphous and fluid character. How could one define the city? I curated a show called Sthalapuranagalu (Place Legends) in 1999 with crowd funding, in which three artists made made large site specific installations at three important historical sites: Ulsoor lake, Victoria statue and Samudaya House. It was the first large such project in an Indian city.

Bengaluru is, I think, the most cosmopolitan and vibrant city in the South, a centre of science and culture.

Pushpamala N

Pushpamala N has been called “the most entertaining artist-iconoclast of contemporary Indian art”.

She received the National Award from Lalit Kala Akademi (1984), Gold Medal at the VI Triennale India (1986), Karnataka Rajyotsava Award (1986) and Jakanachari Award (2016).

Her works have been shown worldwide and are in major museum collections such as Tate Modern, London; Centre Pompidou, Paris; Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York; National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA) and Kiran Nadar Museum of Modern Art, Delhi; and Museum of Art and Photography (MAP), Bengaluru. She was the Artistic Director of the Chennai Photo Biennale, 2019.