Vidhana Soudha Grandeur in Granite

Vision

© Noppasin Wongchum | Dreamstime.com

For over five decades, the offices of the Government of Mysore co-existed with the High Court in the Attara Kacheri. In addition, new office buildings such as the New Public Office and PWD Office were constructed to tackle the problem of inadequate space. Many government departments functioned out of rented buildings scattered across the city. Soon, the High Court located in the southern wing of the Attara Kacheri and the two Houses of Legislature needed more space and it was decided to construct a new, dedicated building for administration called ‘Vidhana Soudha’.

The site chosen was right across the Attara Kacheri built by the British in 1881. The spacious ground called Residency Compound, sloping gently from north to south, was situated between the city and cantonment area. It was also close to the Old Public office and many other existing Government buildings around the area. Today, the two buildings stand facing each other as symbols of the old versus new, colonial imperialism versus independence and oppression versus freedom.

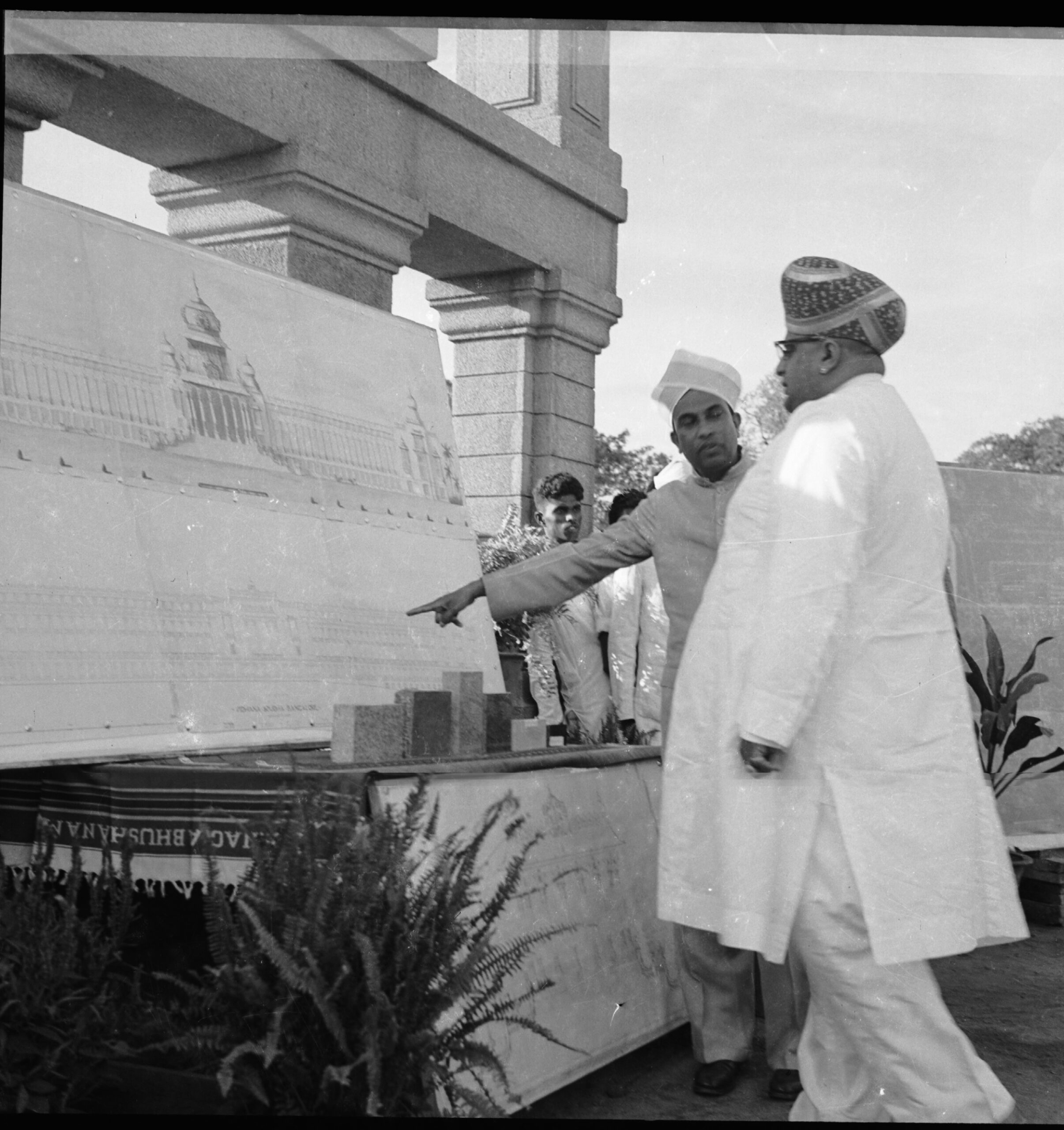

The foundation of this mega project was laid by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru on July 13, 1951 when Kyasamballi Chengalaraya (KC) Reddy was the Chief Minister of Mysore. The original design was on a smaller scale with an initial estimated cost of ₹30 lakhs, but the construction did not start during the term of KC Reddy. KC Reddy was in office until March 1952, when he was succeeded by Kengal Hanumanthaiah.

Aerial View of Vidhana Soudha and Attara Kacheri.

Architect

© Md Sarfaraz | Dreamstime.com

Very few people have the chance to be identified with a famous landmark that has become the de facto symbol of a city. It is even more unusual that the person hailed as the architect of this landmark has a degree in law and is a politician by profession.

By a combination of vision and zeal, Kengal Hanumantaiah seized an opportunity to build something of inestimable value for Bengaluru and Karnataka. Considering that India was just four years old after Independence and taking its first steps as an independent nation, the scale and size of the project, the formation of a team to work together for several years and perseverance to complete a mammoth project against the headwinds of criticism was a stupendous achievement.

Hanumanthaiah was born on February 14, 1908 in Lakkappanahalli, a small village near Ramanagara between Bengaluru and Mysore. His parents Venkata Gowda and Nanjamma came from a farming family in a remote village far away from any city. Hanumanthaiah once commented that his parents had probably not even seen a gram panchayat (Village Committee) in their lives. He studied in Maharajas College in Mysore, obtained a law degree from then Poona Law College before starting practice in 1933. He was imprisoned seven times during India’s freedom struggle, became the second Chief Minister of Mysore state and eventually a member of Lok Sabha for 10 years from 1962.

Design

© Lakshmiprasadlucky | Dreamstime.com

Once Hanumanthaiah took office as Chief Minister on March 30, 1952, he took charge of the design and construction. He desired to have the Legislative Hall, chambers, minister’s offices, secretary offices, library in the same building. The design was changed from one floor to a three floor building and the cost went up to ₹50 lakhs. For him, it was more than just a building and he invested his passion, mind, power and pride in making it a reality. He was involved in all aspects of the construction from location, design, engineering to selection of artisans, paintings and material.

In an interview he said “Right from my student days I was proud of Indian culture. Many people were influenced by western literature, art, music over our own and this trend also extended to buildings. We had wonderful architecture as seen in Belur and Halebid. As Chief Minister when I got an opportunity to build Vidhana Soudha, I was keen to use our own architectural style and feel very proud of it”

The architectural design of the building is based on Dravidian Renaissance style which flourished in South India during tenth century AD. The square and polygonal pillars with richly carved base and capital, deep friezes (middle section of the entablature, the horizontal structural element that sits atop the columns), kapota (cornice – a strip of plaster, wood, or stone which goes along the top of a wall or building, usually found in temples of South India), chaitya arches (circular or horseshoe arch that decorates many Indian cave temples and shrines), heavy pediments (decorative gable, usually triangular in shape over doors and windows), domical finials (a distinctive ornament at the apex of a roof, pinnacle in a building), pillared halls, intricately carved door frames and doors are some of the special features of the design.

© Ajay Bhaskar | Dreamstime.com

© Gemini Prostudio | Dreamstime.com

© Virgokishore | Dreamstime.com

© Shaikh Mohammed Meraj | Dreamstime.com

Plan

© Amith Nag | Dreamstime.com

Vidhana Soudha is rectangular in plan, measuring 700 feet north to south and 350 feet east to west, with two patios measuring 230 square feet each. The northern wing with four floors is 63 feet 6 inches in height. The southern wing, which also consists of a cellar, is 73 feet 6 inches from ground level.

The central wing with the Banquet Hall on ground floor and the Legislative Assembly Hall spanning first and second floors is 112 feet high. The front elevation is highlighted by the central dome of about 45 feet in diameter about 200 feet from ground level.

The Chief Minister’s chamber and the Cabinet Room are on the third floor of the Northern wing. The southern wing accommodates the safe room of the State Huzur treasury and the National archives in the cellar. The Records department and the State Huzur treasury are located on the first floor and the Legislative Council spans the first and second floors.

The Banquet Hall is one of the largest rooms in the central wing measuring 129 feet by 195 feet with a seating capacity of about 800 people.

The Legislative Assembly Hall measuring 125 feet by 133 feet by 40 feet can accommodate 250 people with a provision to expand it to 300 by seating adjustment. The Hall is enclosed by teak wood paneling with etched glass above. The Hall also boasts of acoustic materials and a state-of-the-art sound system. Each member seat has a self controlled mike system (with the master control at the Speaker’s desk) and bi-lingual headphones. The Visitors Gallery itself can accommodate about 600 people at a time.

The Legislative Council Hall is much smaller at 78 feet by 100 feet by 40 feet with seating capacity for 88 members. The Visitors Gallery here can seat about 250 people.

Outside, the grand staircase steps were 204 feet wide and 70 feet in height leading directly to the foyer on the first floor. In addition there are six internal staircases, four passenger lifts and a goods lift in the southern wing.

In all, the architects and designers visualized and built an imposing building that reflected the grandeur of local style of architecture using local materials. A modern building just built on functional principles would have never depicted a period when the rule of the state passed from the royalty to the common man.

© Virgokishore | Dreamstime.com

© Virgokishore | Dreamstime.com

© Srikanth BS | Dreamstime.com

© Noppasin Wongchum | Dreamstime.com

Construction

© Amith Nag | Dreamstime.com

The engineer in charge of the construction was BR Manickam. Born in the year 1909, he was an exceptionally brilliant student obtaining his Engineering degree from the Government Engineering College in Bengaluru in 1930. In 1948, he obtained an MS degree in Architecture and Town Planning from the famed Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) in Chicago. On his return to Bengaluru in 1949, he became the Chief Government Architect and subsequently the Superintendent Engineer in 1955. Apart from Vidhana Soudha, he was responsible for many famous public buildings such as Ravindra Kalakshetra, Indian Institute of Science and Hubli Medical College to name a few. He retired in April 1964 after serving in the State Public Works department for over 30 years but passed away a month later on May 31, 1964 at the age of 55.

It is said that during the time of Hanumanthaiah as Chief Minister, there was no scope for contractors lobby or shoddy development work even in public buildings. The responsibility of constructing Vidhana Soudha was handed over to the State Public Works department. The story goes that, before the construction work started, Hanumanthaiah and the Chief Engineer of the project went to the Kengal Anjeneya Swamy temple, asked for two cups of milk, took a vow to work honestly, sincerely and ethically in front of the deity and drank the milk. Hanumanthaiah would go to the site every day at 5 am in the morning and often incognito to check on progress and if there was misappropriation of materials.

Considering the large amount of stonework in the construction, experienced chiselers and carvers were recruited from South India and it was estimated that about 1000 chiselers would be used continuously for over a year. In 1954, about 2000 labourers including about 200 convicts were working at the building site.

To illustrate the wages per day during construction , a mason was paid around ₹3, a carpenter around ₹3.75, a polisher around ₹2, painters around ₹2, a male ‘coolie ‘ around ₹1.50, a female ‘coolie’ around ₹1 and a watchman around ₹1.50. Fittingly for a building that was called ‘Poetry in Stone’, chiselers were one of the highest paid at ₹3.50!

During construction, Hanumanthaiah took eminent personalities like Sir M Visveshvaraya and Sir Mirza Ismail to the site for their opinions and suggestions. When Rashtrakavi KV Puttappa visited the site, Hanumanthaiah is reported to have told him”You have created poetry from words. I have created poetry out of stones”. It was often said that Hanumanthaiah was familiar with every stone and every worker that was used.

The site had fairly stiff red soil. The foundation made of reinforced concrete varied in thickness and depth depending on the load above. The foundation soil consisted of hard gravel and disintegrated soft rock and in view of the heavy intensity of loads on the main load bearing walls, a continuous raft foundation ( a large concrete slab which can support a number of columns and walls) was used to limit the pressure on the soil to 1.5 tons per square feet even though it can withstand up to 3 tons per square feet. The foundation for the main dome extended 15 feet below the ground level.

The main structure was made of carefully chosen grey granite sourced from places like Bettahalasur, Arahalli and Hesaraghatta around Bengaluru. Green bluish granite from Mallasandra was used for lining the interior quandrangle. Red porphyry (a hard igneous rock containing crystals, usually of feldspar, in a fine-grained, typically reddish groundmass) from Magadi and black granite from Turuvekere was used for decorative work. Reinforced concrete was used for flooring, lintel and stairs. Mysore teak wood was used for doors and windows. Sandalwood carvings were extensively done by Gudigars, artisans from Shimoga, Sorab and Sagar area that for generations have been engaged in sandalwood and ivory carving.

Plain cement tiles were used for flooring in office rooms, mosaics of different colours in foyers, galleries, lobbies and minister’s rooms and the Banquet Hall. Walls and ceilings were finished in lime plaster on which plastic emulsion paints were applied. The four corners of the building have towers with domes topped by kalashas as finial.

The central dome measures 45 feet in diameter at the base and is about 30 feet in height. It was claimed to be the largest single unit construction in India. The total load of the dome, tower, columns and foundation ring beam and raft at the foundation level is nearly 5800 tons. The tower in front at the center of the building is about 150 feet high supported on 3 feet diameter RCC columns in the front foyer forming a circle of 60 ft diameter. Each of these eight columns support a load of 700 tons at the base. The dome was designed to withstand a wind load (the force exerted on a surface by the wind) of about 50 lbs per square feet. The central dome was originally planned to have an observation deck to get a panoramic view of the city.

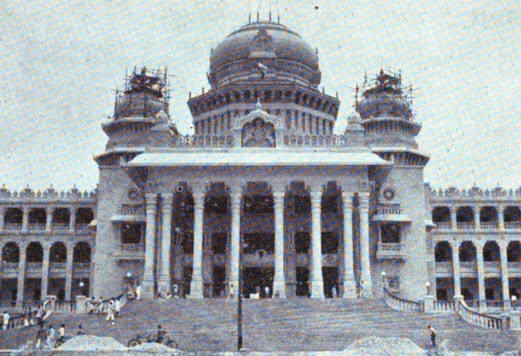

The finial of the dome is a 30 feet high Ashoka emblem made of 1/16 inch copper sheet. It is also designed to resist a wind load of 50 lbs per square feet (equivalent to hurricane winds). Interestingly, the building was opened for use even before the main dome and tower were completed. A noteworthy point is that everything was designed and constructed by architects and engineers from the state of Mysore using mostly indigenous materials from the state. It consumed 3800 tons of steel and 17500 tons of cement.

A committee of experts was constituted to advise on decorations. For example, sayings of seers and saints were planned to be engraved into the cornices. For this, a sub-committee consisting of famous writers Masti Venkatesha Iyengar, C K Venkataramaiah. KV Puttappa (Kuvempu), AN Krishna Rao (Anakru), Asthana Vidwan B Shivamurthy Sastry and others were formed. Various proposals to use statues, paintings, murals were considered. Special niches were included in the building design for installing busts of national and state leaders. Donations amounting to around ₹75000 were used to acquire paintings and statues for this purpose. The words ‘Government work is God’s work’ was engraved on the front entrance.

Along with the building, an elaborate garden was planned all around it. The central boulevard in front was to be called ‘Vidhana Veedhi’ (Avenue of Legislature) with two driveways separated by a central green strip. The garden was laid out in 1958 by the department of horticulture and is spread over 50 acres. Before other structures and roads were built, it also had a spectacular view of Raj Bhavan.

Amidst all this lavish and elaborate detail, utility of space and functionalism was not overlooked. Modern building materials and techniques were used for a strong structure.

On October 14 1956 the auspicious day of Vijayadashami, Vidhana Soudha was inaugurated during the term of Chief Minister Kadidal Manjappa.

On December 19, 1956 the Legislative Assembly and Legislative Council of the newly formed Mysore state started a 10-day session for the first time in the newly constructed halls in Vidhana Soudha in Bengaluru. On the same day, in the afternoon Sri Jayachamarajendra Wodeyar, Governor of Mysore addressed a joint session in the Legislative Assembly Hall.

The Administrative Reforms Commission of the Government of India conducted a study and the report considered Vidhana Soudha to be a role model for all government buildings even a decade after its completion. In the section about government buildings, it noted that

“It has appeared to us, the design of most buildings meant for housing Government offices follow hitherto patterns not very different in vogue from decades ago. These patterns are not utilitarian nor are they in accord with present day architectural practice. A refreshing contrast is provided by Vidhana Soudha in Bangalore which combines utility and appearance. Mysore is the only state that has a building which houses both the Assembly and Secretariat. The resulting convenience to ministers, legislators and officials is considerable. The rooms for use by Secretariat officials and staff let in a lot of daylight thus considerably reducing dependency on electric lights during working hours. Vidhana Soudha is excellently designed from the aesthetic point of view also. The thousands of people who come to see the building from outside and relax in the grounds around are themselves a tribute to the beauty of the building.”

It is hard to imagine in these days of high security, but Vidhana Soudha was open to the public and one could visit and spend time on the steps or in the gardens. On weekdays, the building was open between 8 am and 9 am in the morning and 6 pm and 7 pm in the evening. On Saturdays it was open from 4 pm to 7 pm and for a full 11 hours (from 8 am to 7 pm) on Sundays and other holidays.

© Nesterenkoilya | Dreamstime.com

© Trinijacobs | Dreamstime.com

© Ajay Bhaskar | Dreamstime.com

© Amith Nag | Dreamstime.com

Controversy

© Virgokishore | Dreamstime.com

Actual expenditure at the end of 1957-58 stood at ₹1.52 crore (₹1,52,76,717) and it was estimated to cost about ₹1.80 crores (₹1,80,00,000) in the end. This was about four times the original estimate of ₹50 lakhs. The Mysore government had to borrow money from the Government of India in the form of overdraft for the excess funds.

What was originally meant to be a 1,74,600 square feet building at ₹26 per square feet construction cost, ended up being nearly 5,00,000 square feet costing five times more.

Many legislators were critical of the money spent on Vidhana Soudha. There were several complaints on the food service by Madras Woodlands Canteen, which had been awarded a three year contract from April 1958 as the sole bidder. Legislative Assembly members wanted to know the comments of visitors in the Visitors Book, whether there were critical comments, especially from visitors of foreign countries. They had lengthy arguments on the floor of the assembly about who can write in the Visitors Books and demanded that this be made available as a printed report to all members.

There were two conflicting views about the building. One section felt that the building was a great benefit despite some extravagance in construction. The other felt that it was a totally unnecessary cost which should have been avoided. In a debate on the floor of the house SD Kothavale (who became speaker later) said,

“Of course I share the view of the common man who says that it is a very imposing and highly artistic building. The gentleman who dreamt this imposing and artistic building deserves congratulations but my approach is rather different. My basic approach to this is whether a building of this nature is the one we should have built. Our country is poor. I would have been satisfied with a business like building on the lines of Bombay Sachivalaya”

A three-member enquiry committee was set up to probe into the project. The members were PP Deo, retired Nagpur High Court judge, M Narasimhaiya, retired Chief Engineer of Mysore and BS Raghavendra Rao, retired financial secretary of Mysore. They started work on August 4, 1956 and submitted its report on December 30, 1956. It was critical of Hanumanthaiah on cost management, seeking permission for escalated expenses and technical deficiencies around submission of accounts. Hanumanthaiah acknowledged some shortcomings but said that none of these were intentionally done.

Even after the report was completed, there were debates about whether the Government had accepted and published it. Hanumanthaiah replied that the report was made completely public and every newspaper both English and Kannada had printed it.

In October 1957, the Government decided to erase the inscription ‘Government’s work is God’s work’ and replace it with ‘Satyameva Jayate‘ (Truth shall prevail) at a cost of ₹7500, but it was not done.

What was ironic was that the man who persevered to build this monument did not function as a minister from Vidhana Soudha even for a single day. Just before unification of the state, Hanumanthaiah resigned as Chief Minister of the state on August 19, 1956 ahead of a no confidence motion and moved to the national political stage.

He passed away on December 1, 1980 at the age of 72. On December 3, 1980, the state cabinet took a decision to install a statue of Kengal Hanumanthaiah in front of his dream building, from where he is united with it forever.

Grand pillars of the Banquet Hall

Sandalwood carved door to Cabinet Room

Memories of a Superstar

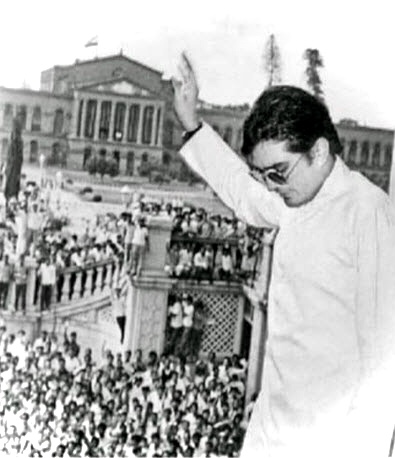

In the 1970s, a phenomenon had swept everyone off their feet in India and Bengaluru was not immune to his charm. Rajesh Khanna had celebrated yet another box office success and was at the peak of his reign. During one of his visits to the city, the Government of Mysore and Mysore Sales International Limited (MSIL) who conducted Mysore State Lottery invited Rajesh Khanna to pick the winning ticket for their Bumper prize at Vidhana Soudha. Of course, this was widely advertised in the newspapers.

Eager to see the super star in person, I pestered my father to take me there. After much persuasion, he agreed. It was on a Sunday morning that I hopped on to the back seat of our scooter and was driven to the venue. A few hundred fans were already assembled at the front entrance near the base of the imposing flight of stairs. The air was buzzing with excitement. Eventually, Rajesh Khanna, trailed by officials and others, came to the upper floor corridor in his trademark Guru kurta, dark glasses and waved at us. Needless to say, the whole world went wild and so did I. He was there for just a few minutes but I ended up with memory that has lasted a lifetime.

An emperor who had captured our hearts, a cheering, adoring crowd below and the people’s palace. What more could one ask for?

– A Bengalurean

Main Image: © Noppasin Wongchum | Dreamstime.com

Sources:

- The Vidhana Soudha at Bangalore, by BR Manickam, BE, MS, M Am Soc, C.E., MASPO, The Indian Concrete Journal, Vol 32 No 1, January 1958

- Some Aspects of Granite Stone Veneering to RCC dome and tower in Vidhana Soudha by MB Krishna Iyengar and DRSM Gupta, The Journal of The Institution of Engineers (India) May 1967 under the Fair Copying Declaration of the Royal Society

- Report of the Study Team on Promotion Policies, Conduct Rules, Discipline and Morale by Administration Reforms Commission, Government of India, Vol I and II, December 1967

- The Mysore Legislative Assembly Debates Official Reports

- The Mysore Legislative Council Debates Official Reports

- Mysore Information Bulletin, March 1954, April 1959

- Eminent Parliamentarian Series – K Hanumanthaiah, Karnataka Legislative Assembly Library