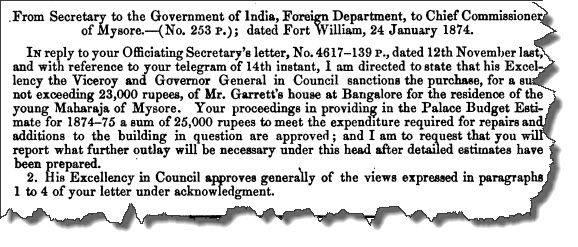

Bengaluru Palace was not built from ground up as a residence for the royalty. Reverend John Garrett’s home that eventually became today’s Bengaluru Palace was approved to be purchased for a sum of ₹23,000 on January 24, 1874

Britain cast a two hundred year long shadow on India, first with the East India Company around 1750 and then a ninety year direct rule from 1858. For much of this time, they adopted a clever tactic of supporting regional royalty to manage their kingdoms or regions, as long they were subservient and filled the Imperial coffers.

The Wodeyar dynasty claim that their rule goes back to 1399, but records show that they gained prominence during the 16th century. However, it is due to British victory over Tipu Sultan in 1799 that the Wodeyars were allowed to restore the monarchy in Mysore, albeit under indirect control. The act of rendition in 1881 was considered as a great act of statesmanship and wisdom by the British. They took credit for restoring the old forgotten dynasty twice and concluded that this act resulted in ‘ardent loyalty and eager partnership with the Imperial government’ even 25 years later, when the Prince and Princess of Wales toured India1.

Traditionally, the Maharajah of Mysore rarely appeared in public except on his birthday and annual Dasara festival. It would also be surprising to learn that the Maharajah usually never travelled out of Mysore or even crossed the Cauvery river. In October 1875, thirteen year old Chamarajendra Wodeyar visited Bengaluru for the first time, accompanied by his British guardian Col. G.B. Malleson as part of his education, grooming and upcoming coronation. 2 Administrative documents of the House of Commons note that the young Prince was a very good student and an able athlete as well.

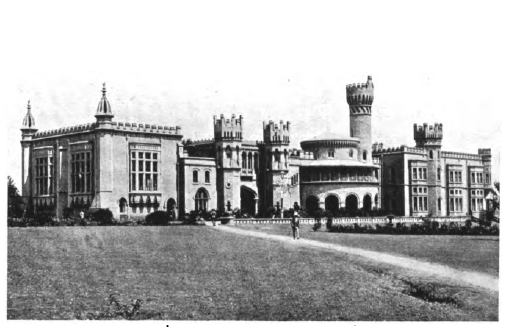

As part of the preparation for the rendition, his British guardians also undertook the purchase of a suitable residence in Bengaluru for the young Prince. Contrary to what is commonly written, the Bengaluru Palace was not built by the Mysore Royal family and the estimted cost of ₹10 lakhs is also debatable. The land and original building belonged to Reverend John Garrett of the Wesleyan Methodist Church. John Garrett was originally from Middlesex in England. He first came to India in 1839 and was involved in promoting religion and education. He retired from Mission activities in 1858 and went back to England. However, he returned to Bengaluru in 1868 and took up the post of Director of Public Instruction in the British Government service. On his return to India, Garrett constructed this building under his own supervision. Even the British thought that while the building was strongly built of stone, it was designed strangely as a castellated structure, very peculiar for a private home.

It was thought to be in an ideal location, away from the Cantonment, European residents, the city and the pete. At the time of purchase, it was in a semi-finished state which would enable additions and changes to be easily made. John Garrett quoted ₹23,000 for the entire house and the large grounds, a sum that was thought to be reasonable. It is not certain if John Garrett built it for his own use as he agreed to defer the sale or lease to others while the British worked to get approvals and the money sanctioned.

Finally, on 24th January 1874, Lord Northbrook, the Viceroy conveyed his approval to Chief Commissioner Sir Richard Meade for purchasing the building for a sum of ₹23,000 along with an additional sum of ₹25,000 sanctioned towards repairs and additions. However, the building was not considered big enough for the purpose of hosting the future Maharajah. While Col. Malleson thought ₹7,000 would be adequate for making additions, Col. Richard Sankey believed a larger budget was needed. The British planned to add more residential space, offices, stables and a picturesque park with lawn. The changes and additions took over an year and was planned to be completed by July 1875. However, even after that it was not likely to be ready for habitation for some more time. The proposal was to have the Prince occupy the completed residence for a short period around Dasara in 1875 and make the final move in early 1876. In addition to the Prince, there were plans to have a tutor from England live in an adjoining house. The master of the Mysore palace school and the Prince’s tutor Narasimha Iyengar would also move to the new “palace” and manage the household which would have an additional seven or eight young boys from the Mysore Royal family.

The total area which is about 45000 square feet in size today, was built in stages over time. The two storied structure in Tudor style consists of fortified towers and turrets. It also has Roman and pointed arches, bastion-like towers and a layout of recesses and projections of many geometric patterns, circle, octagon and square.

Bengaluru Palace interiors today

Click on each image above for a larger view

The interiors are grand with floral and geometric designs lit by glittering chandeliers. The palace had carpets purchased from France and England, heavy furniture from London, decorations by European artists, and the more ornamental furniture from Paris.4 In fact, it was said that there were few traces of any Indian architecture or furnishings. The grandeur was said to even put Buckingham Palace in the shade.

Even though the palace was generally considered as out of bounds for the public, one could submit an application and tour the halls at leisure by special permission when the Maharajah was not in residence.5

The palace was extended over time with additions and improvements. Between 1881 and 1886, about ₹ 73,624 (approximately ₹40,000,000 in today’s money) was spent from a special ‘Palace Fund’ for extending the palace building, constructing a cottage in the grounds, building new cooking and dining apartments and improving the water supply to the palace and the gardens. Some of the extensions were ‘in Hindu style with an open quadrangle in the centre’ for the Maharani (Queen). In the following five years between 1890 and 1895, a further ₹98,000 (approximately ₹52,000,000 in today’s money) was spent on maintenance of the palace.

Some of the palace work was assigned to T Muniswamy Appa, an engineering firm established in 1894 in Bangalore. He was responsible for construction of many famous landmarks in the city like the Shankar Mutt, parts of the Government Central College and a bridge (then the longest and heaviest) across the Lakshmana Tirtha river in Mysore.

Everything in the palace was of exquisite design. As an example, a door from the palace made from ebony and inlaid with ivory and brass was submitted by Mysore as an entry in the Calcutta International Exhibition in 1883-84. It won the ‘First Class certificate and Gold Medal’. J.W. Morris author of ‘A Guide to Bangalore and Mysore Directory 1905′ called it as the finest palace on this side of India.

During the reign of the Mysore royals, it was used not only as the royal residence but also as a venue to celebrate the arts. It is said that Nalvadi Krishnaraja Wodeyar arranged a concert for Beethoven’s centenary in 1920 with many famous artists along with the palace orchestra.6 The Maharajah was an ardent lover of both Indian and European music. The English Band orchestra played European classics. There was also a ‘Palace Band Service’ that played for many distinguished guests including Viceroys.7

Apart from arts and entertainment, it was also used for hosting visiting dignitaries and also for meetings of serious nature. In February 1946, Viceroy Lord Wavell toured drought affected areas of Mysore and then presided over a Food Conference at the palace. 8

The expansive gardens and grand interiors have also been a location for many Indian and International movies. Notable among them were E.M. Forster’s ‘A Passage to India’ by David Lean and Krishna Shah’s flop crime caper ‘Shalimar’ starring Rex Harrison and Dharmendra.

Between the years 1950 and 1971, the royal families all across India retained their palaces and respect of the common man, but were politically sidelined. In 1971, the privy purse was abolished and the tradition of Maharajahs became a thing of the past. Successive governments tried to take over the properties of the Mysore royal family considering the rapidly increasing land value. In the 1970s, the government ruled that the Mysore royal family could perpetually use the palaces from generation to generation, but not sell any of them in whole or in part. Then Minister of Railways Kengal Hanumanthaiya, who built the Vidhana Soudha, even said that Indian Railways would buy the palace and convert it into a railway station rather than let it be sold to private parties.9 He said that the Maharajah had to be rescued from the clutches of a few unscrupulous people around him. In 1974, when Jayachamarajendra Wodeyar died in the palace, the Devaraj Urs government locked it up. 10

Hidden deep behind the high walls, the palace in Bengaluru was never really in view of the common man nor was it revered as much as the Mysore palace.

The legal battle with the descendants of the Mysore royal family continues till today. In the meantime, the palace and its sprawling grounds are being commercially used for exhibitions, riding schools and weddings among other things. Anyone can now proudly claim that they got married in a palace (or at least near it) by renting it for a few hours.

Bengaluru Palace is a shadow of what it was in its prime time. Photography and videography is not allowed inside the palace building now and the reason offered is that the owners do not want photographs freely available online. It seems a bit hollow because every publicly accessible nook and corner of the palace has already been captured and shared widely. The more plausible reason could be to avoid the spotlight on the current state of the palace with its crumbling, unmaintained interiors. The gardens look sad and stray dogs (with entire litters) are all around the building. Sadly, it has become just another lucrative piece of real estate in the heart of the city. The glory has gone with the royalty.

Credits

Geometric Turrets, Exterior Wall with creeper, Jockey Weighing Chair, Palace from the Garden, Red chandelier, Corridor with arched pillars, Artistic wooden partition and furniture, Open Courtyard, Carpet Design, Artistic Pillars, Iron metal grill designs – Copyright Selvam Raghupathy | Dreamstime.com

Stairs with framed photographs on the wall, Yellow Pillars with arches, Palace Hall – Copyright Saiko3p | Dreamstime.com

Artistic Pillars – Copyright Jayk67 | Dreamstime.com

Metal pillars with artistic designs – Copyright Erhard Wolloner | Dreamstime.com

Dazzling Lighting – Copyright Rudra Narayan Mitra | Dreamstime.com

Cannon at the palace – Copyright Maneesh Upadhyay | Dreamstime.com

All images are copyright of respective owners and cannot be reproduced without permission.

References

1-The Royal Tour in India – A record of Tour of T.R.H. The Prince and Princess of Wales in India and Burma, from November 105 to March 1906 by Stanley Reed, Special Correspondent of the ‘Times of India’ Page 364

2-Princely India Re-imagined – A historical anthropology of Mysore from 1799 to the present by Aya Ikegame published by Routledge Educating the Maharaja Pages 57-66

3-Karnataka State Gazetteer Bangalore District Page 945

4-Indika – The country and the people of India and Ceylon by John F Hurst Harper & Brothers Franklin Square New York 1891 Chapter XXX A Run Into Mysore

5-A Handbook for Travellers in India, Burma and Ceylon – John Murray London

6-Music and Empire in Britain and India by Bob van der Linden, Palgrave Macmillan Page 17

7-Studies on Dewan Sir Mirza Ismail Collection of Seminar Papers Published by Mythic Society

8-Indian Information Volume 18 Page 213, 1946

9-Mysore Legislative Assembly Debates Official Report Page 121

10-The Illustrated Weekly of India, 1986 Volume 107 Issues 39-51 Page 31